Campaign Visits Database

The Campaign Visits Database (CVD) is an original dataset of presidential campaign visits since 2008. I created the CVD in order to analyze the strategy and effects of campaign visits in my new book, I’m Here to Ask for Your Vote. I am providing it here, free for download, as a resource for scholars and others who may be interested in studying campaign visits.

To download the CVD, click here.

The CVD presents data first by visit and then by county. “By visit” data report when (date, year) and where (address, venue, city, county, state, designated market area) each visit took place, and provide at least two documentary sources. (Note: Links will go dead over time; I will update occasionally.) “By county” data report the number of visits per year made by each candidate to a given county or state.

I define campaign visits as any public, in-person appearance apparently organized or initiated by the candidates or their campaign, for the purpose of appealing to a localized concentration of voters. This definition excludes nationally-oriented events (e.g., national party conventions, national conferences, presidential debates, and historical commemorations), as well as events in which the public and/or the press are prohibited from participating (e.g., private fundraisers, closed press conferences).

More details on the Campaign Visits Database—including rationale, methodology, and descriptive results—can be found in my book, I’m Here to Ask for Your Vote.

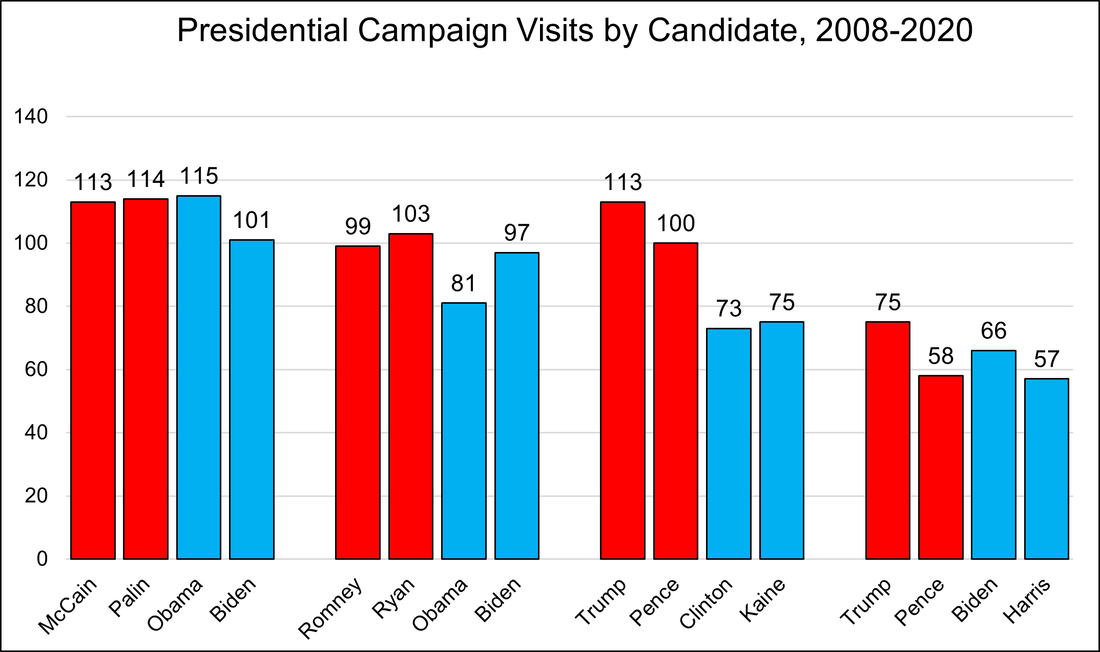

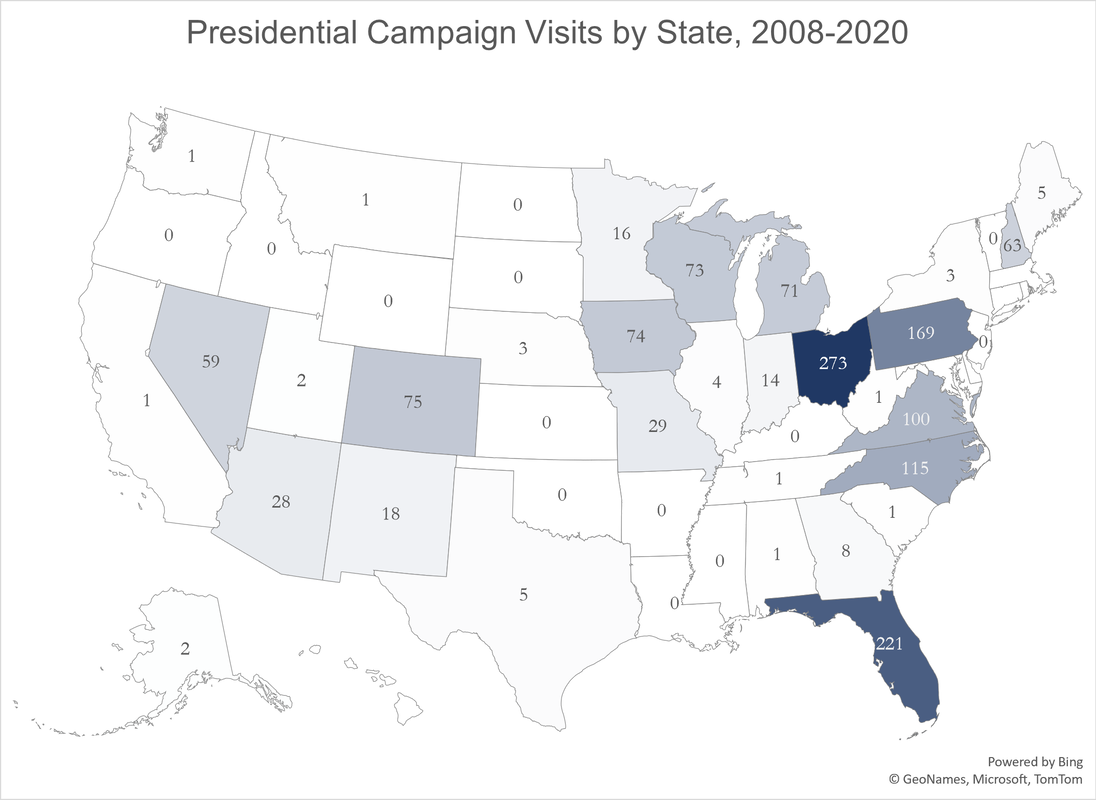

My book uses the CVD to answer perennial questions about campaign visits—for instance, which candidates were most active on the campaign trail? And where did they go? Here are two examples…

The Campaign Visits Database (CVD) is an original dataset of presidential campaign visits since 2008. I created the CVD in order to analyze the strategy and effects of campaign visits in my new book, I’m Here to Ask for Your Vote. I am providing it here, free for download, as a resource for scholars and others who may be interested in studying campaign visits.

To download the CVD, click here.

The CVD presents data first by visit and then by county. “By visit” data report when (date, year) and where (address, venue, city, county, state, designated market area) each visit took place, and provide at least two documentary sources. (Note: Links will go dead over time; I will update occasionally.) “By county” data report the number of visits per year made by each candidate to a given county or state.

I define campaign visits as any public, in-person appearance apparently organized or initiated by the candidates or their campaign, for the purpose of appealing to a localized concentration of voters. This definition excludes nationally-oriented events (e.g., national party conventions, national conferences, presidential debates, and historical commemorations), as well as events in which the public and/or the press are prohibited from participating (e.g., private fundraisers, closed press conferences).

More details on the Campaign Visits Database—including rationale, methodology, and descriptive results—can be found in my book, I’m Here to Ask for Your Vote.

My book uses the CVD to answer perennial questions about campaign visits—for instance, which candidates were most active on the campaign trail? And where did they go? Here are two examples…

Question #1: Was Joe Biden “hiding in his basement” in 2020? No. In fact, he made more campaign visits than Mike Pence or Kamala Harris (and only nine fewer than Donald Trump).

Question #2: Do candidates ignore “small” states, by visiting only large battlegrounds? Yes and no. They visit large battleground states the most (e.g., Ohio, Florida, Pennsylvania). But they also visit small battleground states (e.g., New Hampshire) while rarely visiting large "safe" states (e.g., California, New York).